Charles Francis Annesley Voysey

During the two decades before the First World War Charles Voysey became arguably the most famous British architect since Christopher Wren. Hugely respected by younger contemporaries, such as Edwin Lutyens, Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott and Charles Rennie Mackintosh – each of whom is perhaps better known than Voysey today – he was equally celebrated internationally. When Frank Lloyd Wright visited England in 1905 he made a point of studying Voysey’s houses and their influence can be seen in Wright’s ‘prairie style’ house designs in North America in the 1920s and 30s.

Born in 1857, the son of a clergyman, and largely home-educated, Voysey had a flair for art and a grandfather who had been a successful architect, two reasons, it seems, why he chose the career he did. He was fortunate to be articled to three of the best architects of his day, John Pollard Seddon, Henry Saxon Snell and George Devey. Astonishingly by the time Voysey established his own practice in 1881 his signature style was fully formed and remained largely unaltered over the course of his career. Voysey built houses which were the embodiment of homeliness – something he described as conveying a sense of peace and security, comfort, ease and simplicity. A house, he said, should be a refuge from the busy world and a ‘port in a storm’.

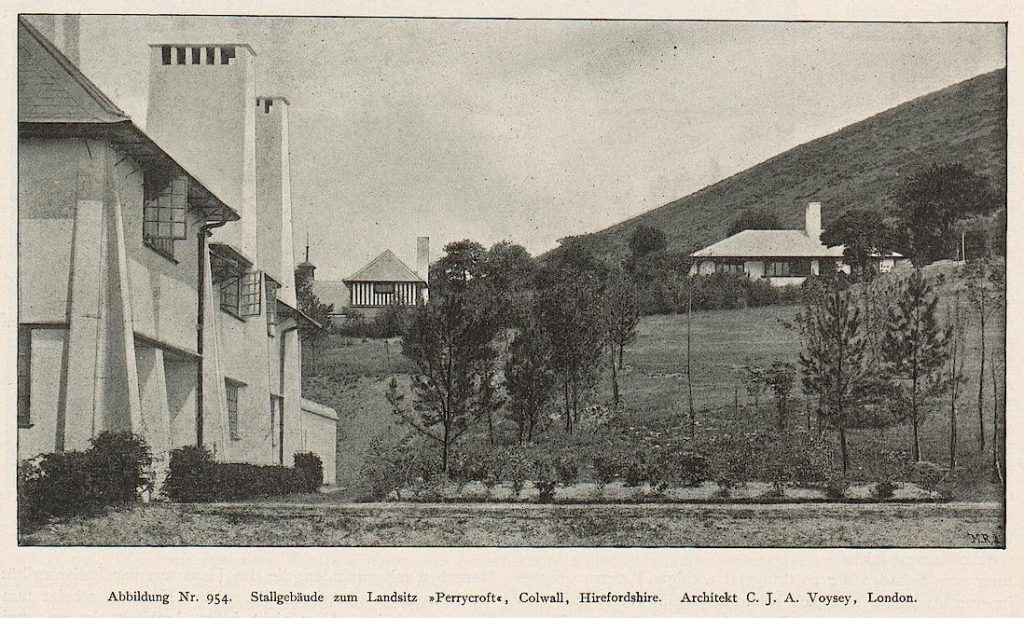

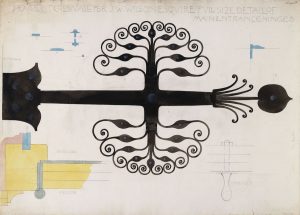

Perrycroft, his first major commission in 1893, exhibits all the features by which he expressed this idea: a large hipped roof with deep eaves sitting like a protective hat over the building and its occupants, casement windows tucked up snugly like look-outs from a keep, sloping buttresses suggesting well-fortified walls, wide doors and low ceilings inside creating a cottage-like atmosphere, and exaggerated chimney stacks redolent more of medieval castles than domestic houses. Voysey imagined a house as a single work of art, with all of its interior detail and contents – from curtains to carpets, fireplaces to kitchen fittings – flowing from the architect’s unifying vision. Even humble details such as window catches and door hinges were designed with care and made pleasing to the eye.

Nostalgia for a pre-industrial medievalism had been shared by the artists and social critics who influenced Voysey, such as Augustus Pugin, John Ruskin and William Morris, but there nothing nostalgic about Voysey’s houses. They are emphatically modern, and yet vernacular traditions – whether a clerestory, a casement or the open-plan ‘living hall’ – are integrated subtly and subliminally into the finished design. No wonder to his contemporaries, as Lutyens said, he seemed to make ‘an old world new again’. Voysey de-cluttered the Victorian sensibility into which he was born. Compared with the detailed and highly naturalistic fabric and wallpaper designs of Morris, for example, Voysey’s birds and flowers have an almost child-like charm and simplicity to them, anticipating Matisse’s cut-outs almost half a century later.

If any architect can be said to have created a ‘national style’ it was Voysey. A walk down any suburban street with houses built between the 1920s and the 1950s will find houses with white roughcast render, large sloping roofs, bay windows, semi-circular porches and possibly mock-Tudor half-timbering. While many of these designs caricatured or debased Voysey’s vision, they stand testimony to the enduring appeal of his vernacular details and his ideal of the home.

Voysey designed over a hundred buildings but it is his large country houses, mainly in the Lake District and the Home Counties, which made his reputation. His style fell out of favour after the First World War and he then lived in relative poverty, subsisting on wallpaper designs and occasional commissions. His reputation recovered in large part thanks to support from the young John Betjeman, then a critic on the ‘Architectural Review’, and in 1939 Voysey was awarded the RIBA Gold Medal. He died in 1941, aged 83.

‘Never look at an ugly thing twice,’ Voysey wrote, ‘it’s fatally easy to get accustomed to corrupting influences.’ According to actor Robert Donut, who married Voysey’s niece, Voysey ‘had a rooted objection to anything that harboured dust or dirt of any description. Therefore there were no unnecessary nooks or crannies in his clothing, not even cuffs to his trouser bottoms. He was clean and prim and gentle, but of firm disposition.’ Just as with his clothes so too with his buildings, Voysey designed houses free of Victorian nooks and crannies and any unnecessary ornament that was likely to gather dust. His influence was far reaching into the 20th Century.